It’s made out of living human cells. Someday they could be yours.

The human heart is special. That’s not some bad poetry: it’s a tricky truth in medical research. Time and time again, drugs that look promising in experiments on animals are no good for humans. And often it’s because a compound that is harmless to a mouse heart is toxic to the human heart. Other rodent organs more closely approximate ours, but the structure and the physics of our hearts—all the way down to the minute details of how calcium ions flow—are simply too different.

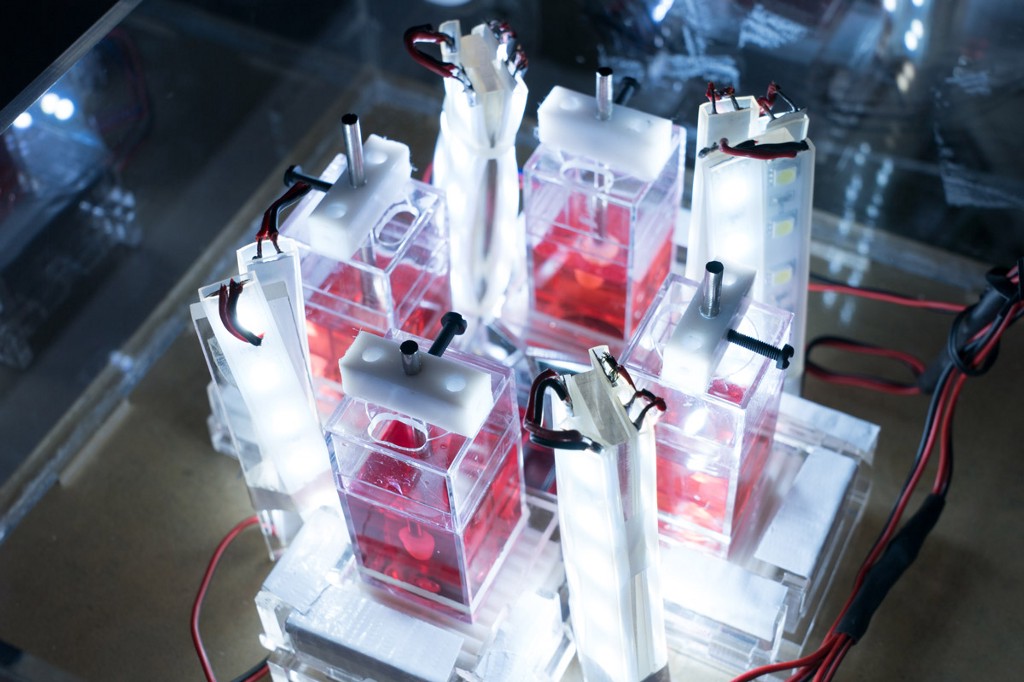

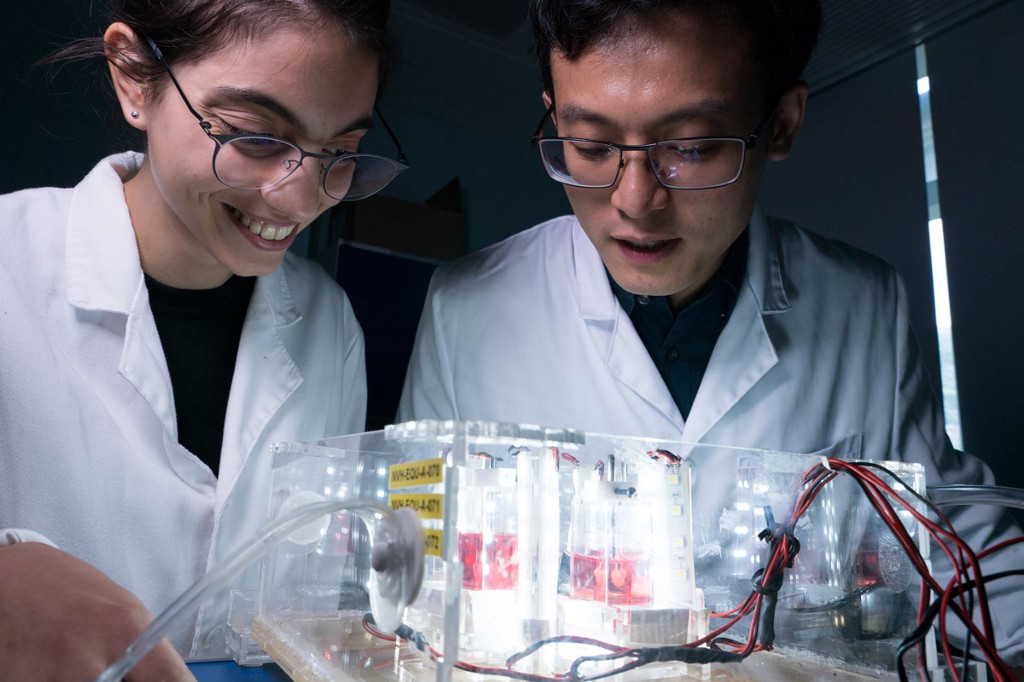

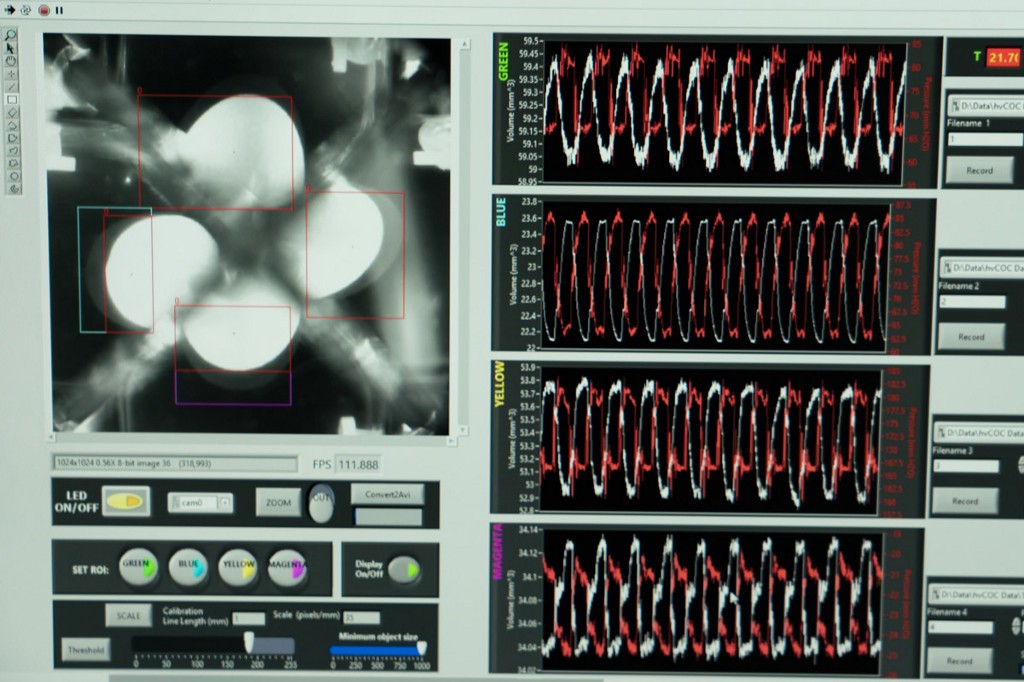

That’s why a company called Novoheart developed this miniature human heart in a jar. OK, it’s just a portion of a heart—an organoid—grown from human stem cells. But it’s hollow and it beats. When any compound is added to the container, researchers can get clues about its safety by analyzing how well the organoid conducts electricity and how strongly it contracts.

One of Novoheart’s first clients is Pfizer, which is studying a drug that might treat a neuromuscular disorder called Friedreich’s ataxia. Novoheart got cells from two people who have the disease and coaxed those cells to grow over about four months into cardiac organoids. Someday, says Kevin Costa, Novoheart’s chief scientist, your doctor might order up organoids from your own cells to help determine which drugs are best for you.