Despite the growing, unsolved mystery of why sperm counts around the world are declining, society still treats fertility as a female issue.

It’s official: Fertility rates are below population replacement levels in most Western countries. Theories as to why and how this happened range from birth control access and cultural issues to secularization, the increasing age of mothers, and child-care costs. But there is also a sinister biological reality afoot. The quality and quantity of men’s sperm dropped by over half in the past fifty years—and no one understands exactly why.

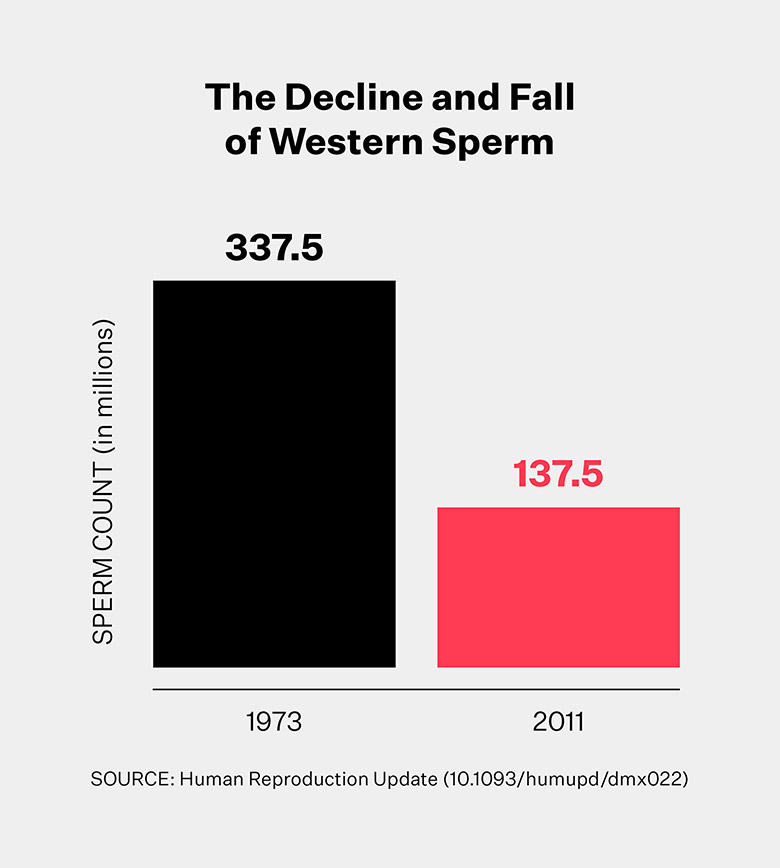

We know that per-milliliter sperm concentration plummeted 52.4 percent and total sperm count dipped 59.3 percent across North America, Australia, New Zealand, and Europe between 1970 and 2011 and shows no sign of leveling off. The limited data available in South America, Asia, and Africa did not reveal the same steep decline, but it cannot be ruled out either. While skeptics claim that sperm counts are technically still in an acceptable range, if the average were to continue to drop at the same rate, then projecting this trend out into the future would suggest that over half of all men in the West could have little to no viable sperm as soon as 2045.

There’s no reason to assume that droop will continue linearly and unabated toward zero—or even that we will ever reach “spermpocalypse,” but it raises the more fundamental question: why is our sperm production falling in the first place? Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals is one leading theory, especially substances like phthalates and BPA that are commonly found in plastics. Combined with smoking, drug and alcohol use, and increasingly sedentary lifestyles, many men’s bodies today are particularly inhospitable environments to manufacture and store sperm.

Shanna Swan, the author of the massive data review that revealed sperm’s collapse, is one of the world’s leading environmental and reproductive epidemiologists. She suggests in her new book Count Down that exposure to chemicals is the primary cause of fertility and sexual development issues for both genders. And these changes are not just happening in humans. Dog semen quality has also dropped, and genital anomalies where animals are born with intersex ambiguity have been observed in reptiles and mammals like otters, as well.

Declining sperm doesn’t just impact fertility. It is a marker of other health trends, like low testosterone levels, tumors, cancer, diabetes, cryptorchidism (undescended testicles), and overall morbidity and mortality. Not great news, since men’s lifespans are five years shorter on average than women’s anyway and dropping at a faster pace [PDF].

The panicked response one would expect to the threat of multi-species infertility and truncated life spans has simply not happened. Even when faced with compelling data, fertility forever seems to remain a female issue.

Big man, little sperm

The relationship between men and sperm is primal. Sperm is a biological yardstick for manliness and virility, and as the narrative goes, how men spread their family names and genes. Women are labeled by obstetrics as “advanced maternal age” when they become pregnant over age 35—or, worse, “geriatric.” For men, however, there is still a widely accepted belief that men can father children into their 80s with no problem—fueled by December dads like Larry King and Mick Jagger. Outside of a vasectomy or condoms, options for male birth control have yet to materialize, so managing rings, shots, pills, hormones, and diaphragms (and their side effects) is also a woman’s problem.

A country’s fertility rate itself is calculated based upon women’s bodies—it is the average number of live births per woman of reproductive age. If help is required for conception, testing typically begins with women’s bodies and eggs in the United States, even though it would be far less invasive and expensive to look at sperm first.

The age of the father is the dominant factor in determining the number of new genetic mutations in a child.

Here is the truth: Infertility is exclusively related to women’s bodies only one-third of the time. One-third of cases are linked to men’s, and another third it either can’t be identified or it’s a combination of both. While women are born with all the eggs they will ever have, men regenerate sperm every sixty-four days through their twilight years. But there’s a hitch—sperm’s quality diminishes as the years pass, just like eggs.

This quality dip in sperm has major biological impacts. The risk of schizophrenia in offspring increases with more advanced paternal age. So does the risk of Down syndrome, bipolar disorder, autism, and childhood leukemia. The age of the father is the dominant factor in determining the number of new genetic mutations in a child. And even though sperm is produced into old age, men experience age-related fertility decline starting around 35, just like women.

Age isn’t the only impact to sperm quality—lifestyle influences it too—yet men are rarely given conception-related lifestyle guidance. Cannabis use, which includes THC and CBD, can hurt sperm counts and morphology, and reduces libido. Smoking in general while trying to conceive hurts the odds of having a healthy pregnancy and the eventual offspring, too. There is no call from the medical establishment for men to stop steroid use or to audit other pharmaceutical drugs that cause harm to sperm. Obesity is also associated with poorer semen quality, and yet we do not urge men to reduce their weight or oxidative stress through exercise before conception either.

Heat is another one of sperm’s nemeses. In insect models, a heatwave just 5–7 degrees Celsius above the optimum temperature damaged male—but not female—reproduction. Heat reduces sperm competitiveness, reduces its lifespan, and the sperm that do survive spawn offspring with shorter lifespans and reproduction, meaning there is a transgenerational impact to these changes. And although we sometimes tell men to avoid saunas and hot tubs while trying to conceive, exposure to laptops, phones in pockets, and heated seats in cars also hurt sperm.

If male fertility continues its decline, assisted reproduction is the way forward for humans. But relying on these treatments is fraught. Denmark, home to the world’s biggest sperm bank, is arguably the most permissive country for in vitro fertilization access. IVF is responsible for 10 percent of all live births in Denmark and unlike the United States, which provides zero federal dollars for assisted reproduction, the government pays—but not for everyone. Women over 40 are not eligible for state-funded assistance and those over 45 are rejected even from private treatments. The United Kingdom’s National Health Service-funded IVF is only offered to women under 43 who have been trying to get pregnant for two years or who have had twelve cycles of artificial insemination. However, even if a woman meets that criteria, there is one more hoop to jump through: a local clinical commissioning group that has the final say. The bill for one cycle of IVF if the National Health Service doesn’t bankroll it starts at £5,000. In the United States, the low end is $10,000 and can exceed $15,000 all-in, which puts IVF treatment out of reach for most.

There are also practical issues, especially for working women. IVF is time consuming. It takes between five and seven office visits to complete one cycle. The odds of a cycle working vary wildly based on age, and typical success rates are just 20-35 percent, which means most couples need several cycles to achieve a live birth. The 10–12 days of hormone shots required to stimulate egg production before retrieval cause side effects like irritation, bloating, and moodiness. And the anxiety related to the big question—will it work?—makes IVF an emotionally draining process for everyone involved.

What’s happening down there? The CDC can’t say for sure.

According to the most recent U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Assisted Reproductive Technology report, male factor infertility was the diagnosis reported for 28 percent of all treatments. While female infertility is broken down into many sub-categories—endometriosis, tubal factor, ovulatory dysfunction, uterine factor, and diminished ovarian reserves—when it comes to men, the only type that the CDC vaguely describes is “male factor infertility.” Categories like sperm motility, morphology, concentration, count, or volume and conditions like varicocele, an enlargement of the veins in the scrotum that causes low sperm production and quality, are not tracked by the individual clinics that report data to the CDC. If they were, we would better understand what’s really happening down there.

The fertility market will grow to $36 billion by 2023, yet consumer-facing companies are largely centered around egg and embryo freezing, at-home hormone tests, and general assisted reproduction. Not a lot in there for men. Without exception, websites feature photos of blissful women, set free by the ability to preserve their fertility for a few more years. Sperm freezing has yet to hit the mainstream, though the same thing we tell women about eggs—your genetic materials change with age—is true for sperm. Men should consider freezing their prime-aged sperm in their twenties to mitigate reproductive risks as well.

Companies that serve the male fertility market and succeed have learned to finesse their messaging away from bro jokes and locker room banter to science and a more serious, empathetic tone. Yet even for companies who find this balance and are successful, over half of the sales are to women who purchase for their husbands. This dynamic is so prevalent that during the checkout process customers are actually asked who the kit is for—you or someone else?

While men are not subjected to ticking clock imagery or heavy-handed headlines claiming their reproductive years are slamming to a close, fear is a reason male fertility testing is often declined. A study of young men in the Swiss military revealed that only 38 percent had sperm concentration, motility, and morphology values that met the World Health Organization’s semen reference criteria, a standardized measure of sperm health. Nearly all Swiss men in this cohort countrywide were invited to participate, yet only 5.3 percent chose to actually do so. Practical issues like access to clinics were cited as reasons they declined, as was discomfort at the donation process and with genital examination. But many also admitted their reservations stemmed from the fact that they were not psychologically ready to learn the results.

Given that men make up half of problems with infertility, we must change the conversation to include them.

The challenge of managing men’s health often returns to the culture of toughing it out. Some 41 percent of U.S. men report that they were told as children that men don’t complain or talk about their health issues. Three out of four men would rather mow the lawn or go shopping with their wives than go to the doctor, and only half even consider a yearly physical or engage in preventive care at all. Even when showing health symptoms or nursing an injury, three in four prefer to wait as long as possible before seeking medical attention.

Knowing we’re fighting such a generalized male resistance to medical oversight, what do we do? The menstrual cycle is an excellent, easy-to-monitor indicator of a woman’s overall health, considered by some to be a fifth vital sign. Sperm functions similarly for men. It follows that a yearly sperm physical taken from the comfort of home may be the easiest way to get men on board with more personalized, preventive health care. Tracking sperm statistics like morphology and motility along with DNA fragmentation, which is common in cases of male infertility, is a good place to start. The data gathered over time would build a more complete, true baseline of what’s going on in men’s bodies, from the individual to the larger population. And perhaps it would tell us more accurately why sperm is declining, and how much of it truly can be tied to chemicals or lifestyle—or if it’s something else entirely.

Men who are concerned about their fertility can take a prenatal vitamin or supplement formulated to help boost sperm quality and quantity when trying to conceive. Selenium and vitamin E may improve sperm motility, morphology, or both and improve the rate of spontaneous pregnancy by nearly 11 percent. The nutrient coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) is an antioxidant that leads to better sperm motility, concentration, and count. Another antioxidant, N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), can improve sperm parameters like count and motility and decrease DNA fragmentation and protamine deficiency. Poor zinc nutrition is a risk factor for low sperm quality and male infertility, making it another simple option for supplementation. Diets rich in antioxidants and omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids like fish are also helpful health boosters.

Down for the count

If the spermpocalypse does come, there are bleeding-edge procedures that may keep the human race alive. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection requires just one sperm, delivered straight into the egg’s outer barrier instead of the millions required during traditional IVF. Gene therapies, tissue freezing and grafting, and sperm cell transplantation could also help salvage male fertility. Induced pluripotent stem cells may completely turn human reproduction on its head. Pioneered by 2012 Nobel Prize-winning Japanese scientist Shinya Yamanaka, this approach takes mature somatic cells in the body and reprograms them into completely different cell types. Induced pluripotent stem cells made headlines when they were used to transform cells from a mouse tail into germ cells that resulted in a litter of mouse pups. We have yet to achieve the same result in humans but the possibilities if we do—from reversing infertility to same-sex reproduction—are mind-bending. And speaking of mice, Israeli scientists recently grew mice embryos in artificial uteruses—a breakthrough that not only paves the way for reproduction outside of the body, but also may help us understand why miscarriages and problems during fetal development happen.

For now, at least, it takes a sperm and an egg to make a human. Given that men make up half of that equation, and half of problems with infertility, we must change the conversation to include them. Governments’ regulatory agencies need to do their duty and hold manufacturers of toxic chemicals accountable. Politicians need to demand more transparency and better practices from those same companies. The CDC and assisted reproduction clinics should track and report the various specific causes of male infertility. Private companies should meet demand and step up their fertility offerings to men. And it’s up to all of us to move this issue out of the shadows. Because unlike eggs, which once damaged are damaged for good, it’s not too late for sperm. With the right interventions, lifestyle changes, and care, we can still reverse course. And with that lift for sperm comes better overall health and longer lifespans for men, which will hopefully be a big enough enticement that they start to voluntarily submit their swimmers for inspection so we can see what’s really going on.

Disclosure: Leslie is an angel investor and advisor to several startups that focus on men and women’s reproductive health, none of which are cited in this article.