Hallucinations are a surprisingly common symptom of Parkinson’s, and new research suggests a way to map and potentially treat them.

After being stranded on the edge of Antarctica for more than a year, famed explorer Ernest Shackleton reported seeing a doppelganger during his marathon 36-hour desperation death march through the mountains and glaciers of South Georgia island. He referred to it as his “divine companion,” helping him cope with the journey’s hardships. Nearly a century later, explorer Ann Bancroft was injured during her 1,900-mile journey across Antarctica, and she also found comfort in the presence of a doppelganger who was uninjured and walking alongside her with ease.

What works for polar adventurers may also help people with Parkinson’s.

Although the majority of patients report being frightened by their hallucinations, especially when they first occur, many patients report not being bothered by them and some even love speaking to their hallucinatory friends, according to one of the authors of a new study in the journal Science Translational Medicine, which identified the neural network in the brain that is responsible for the hallucinations. Their work may help scientists understand how hallucinations arise and can help in the treatment of the cognitive decline that often accompanies Parkinson’s disease.

The hallucinatory side of Parkinson’s

If you are surprised that people with Parkinson’s have hallucinations, you are not alone, according to Rachel Dolhun, a board-certified neurologist and movement disorder specialist who is the communications chief at the Michael J. Fox Foundation and was not involved in the new research. “Most people are familiar with the movement disorders associated with Parkinson’s disease, such as tremor, limb rigidity, or gait and balance problems. They are not as familiar with hallucinations or sleep issues, or mood changes that Parkinson’s disease patients often develop,” she says.

According to the Parkinson’s Foundation, the non-motor symptoms of the disease can include attention disorders, language difficulty, memory loss, dementia, the loss of smell or taste, mood disorders, insomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness, depression, anxiety, apathy, and delusions—as well as hallucinations.

“This can be of great concern if a Parkinson’s disease patient tries to stop a perceived intruder.”

In people who have more advanced cases, hallucinations, thinking problems, and dementia are more common, Dolhun says. “Adding to the confusion is that some of the drugs used to treat motor symptoms can cause memory problems as well as hallucinations.”

“The hallucinations can range from seeing a dead loved one [to] children playing on a playground,” Dolhun says. “Some patients see them as benign and don’t worry about them. Others are frightened.”

She notes that some Parkinson’s hallucinations can impact a person’s safety and scare the wits out of their family. One common one is when a person believes an intruder is invading their home. “This can be of great concern if a Parkinson’s disease patient tries to stop a perceived intruder,” Dolhun says.

What can be done to lessen the impact of hallucinations? Dolhun recommends that people talk to their physician about adjusting their medications, try to make a calm environment, and limiting exposure to news or violent shows. “However, some patients will need to be put on antipsychotic medications to control the hallucinations,” she says.

Estimates of how many people with Parkinson’s suffer from hallucinations vary, and Dolhun says that one reason is that many people don’t discuss them with their doctors. “Some patients are embarrassed, so it is hard to say exactly how many hallucinate—most researchers feel it is between 20 percent to 50 percent,” she says.

According to the Parkinson’s Foundation, nearly one million people in the United States are living with the disease and approximately 60,000 Americans are newly diagnosed each year. There are more than 10 million people worldwide living with Parkinson’s.

What the new research shows

Olaf Blanke is founding director of the Center for Neuroprosthetics at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland, and the senior author of the new study. He and his colleagues used a new robotic diagnostic tool that captures sensory and motor processing through brain imaging to determine the severity of the progression of the disease by safely provoking hallucinations in Parkinson’s patients.

“Patients tell me they feel like someone brushed against them.”

In Parkinson’s disease, hallucinations are among the most disturbing non-motor symptoms. The association between formed visual hallucinations and a more severe form of Parkinson’s disease with cognitive decline and dementia is relatively well known. The most common and amongst one of the earliest hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease, is the “presence hallucination,” the sensation of another person being present and nearby when no one is there. “Patients tell me they feel like someone brushed against them,” Blanke says.

Blanke and his colleagues studied the behavioral and neural mechanisms underlying symptomatic presence hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. The researchers induced the presence hallucination in the MRI scanner by means of robotically mediated sensorimotor stimulation to trigger the occurrence of symptomatic presence hallucination in these patients.

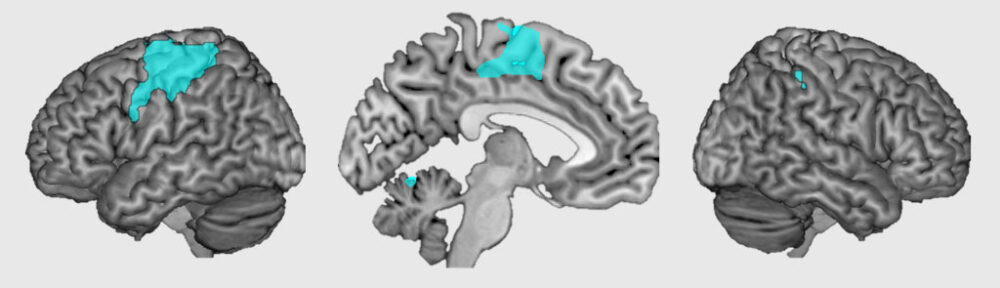

Blanke says robotics coupled with an MRI can map presence hallucinations in the brain and identify a pattern of neural connectivity which is disrupted in individuals with Parkinson’s. By combining brain scans from healthy people with those of people with Parkinson’s and data from people without Parkinson’s who suffer from other neurological conditions that cause presence hallucinations, they identified the specific network of fronto-temporal brain regions associated with presence hallucinations.

“The possibility to induce presence hallucinations while the patient is in the MRI machine allowed us to investigate online the brain networks associated with it,” Blanke says. “We found that the functional connectivity within this fronto-temporal brain network of brain scans at rest predicted whether a patient with Parkinson’s disease also suffered from presence hallucinations.”

Capturing the neural activity

Blanke is currently conducting a large clinical trial to confirm his results and extend the behavioral and neuroimaging data to define further subgroups of patients and investigate the possible relation between presence hallucinations and other forms of hallucinations, such as auditory, tactile, and olfactory hallucinations, as well as the possible relation between presence hallucinations and cognitive decline. His group also plans to further adapt the robotic technology in combination with magnetic resonance imaging with the goal of “capturing” the neural activity associated with hallucinations while they occur. He is also adapting and improving the robotic technology and is working on developing a fully wearable system.

Blanke hopes that in the future, an early diagnosis of presence hallucinations may help physicians to adapt treatments and allow early interventions targeting specific forms of Parkinson’s disease and help to conduct a more homogeneous selection of patient samples for specific cognitive trials.

Dolhun says that the Michael J. Fox Foundation is very interested in artificial intelligence, robotics, and other technology that can enhance traditional treatments, and Blanke’s research is important in that regard. “I hope this research will lead to better treatments and help us predict which Parkinson’s disease patients will develop hallucinations.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated on 9/29/21 to reflect the correct name of the Parkinson’s Foundation in the fifth and eleventh paragraphs.